-

- marketing agility

- Teams

- Organizations

- Education

- enterprise

- Articles

- Individuals

- Transformation

- Solution

- Leadership

- Getting Started

- business agility

- agile management

- going agile

- Frameworks

- agile mindset

- Agile Marketing Tools

- agile marketing journey

- Agile Marketers

- organizational alignment

- People

- Selection

- (Featured Posts)

- agile journey

- Metrics and Data

- Kanban

- strategy

- Resources

- Why Agile Marketing

- agile project management

- self-managing team

- Meetings

- agile adoption

- scaled agile marketing

- tactics

- Scrum

- scaled agile

- agile marketing training

- agile takeaways

- Agile Meetings

- agile coach

- Agile Leadership

- Scrumban

- enterprise marketing agility

- state of agile marketing

- team empowerment

- agile marketing mindset

- agile marketing planning

- agile plan

- AI

- Individual

- Intermediate

- Team

- Videos

- kanban board

- Agile Marketing Terms

- agile marketing

- agile transformation

- traditional marketing

- FAQ

- agile teams

- Agile Marketing Glossary

- CoE

- agile

- agile marketer

- agile marketing case study

- agile marketing coaching

- agile marketing leaders

- agile marketing methodologies

- agile marketing metrics

- agile pilot

- agile sales

- agile team

- agile work breakdown

- cycle time

- employee satisfaction

- marketing value stream

- marketing-analytics

- remote teams

- sprints

- throughput

- work breakdown structure

- News

- Scrumban

- agile brand

- agile marketing books

- agile marketing pilot

- agile marketing transformation

- agile review process

- agile team charter

- cost of delay

- hybrid framework

- pdca

- remote working

- scrum master

- stable agile teams

- startups

- team charter

- team morale

- user story

- value stream mapping

- visual workflow

Getting Agile to scale is tricky in any context, and Agile marketing is no different.

Complex scaling models designed to help dozens of development teams deliver massive software updates over a period of many months feel like overkill, yet enterprise marketers need something more than basic frameworks like Kanban or Scrum to tackle their multi-team initiatives.

We’ve seen this struggle manifest in client after client over the years, so AgileSherpas has developed an Agile framework designed to help marketers implement Agile ways of working across multiple teams.

We call it Rimarketing, after the Japanese phrase Shu Ha Ri (if you’re curious about the origins of this name, jump here for an explanation).

If you just want to see how it works -- and how it can help you improve collaboration, reduce handoffs, and decrease the time you spend waiting for feedback -- read on.

(For even more on how this works, check out my latest book Mastering Marketing Agility, which will tell you all you ever wanted to know about this framework.)

4 Steps to Scaled Agile Marketing

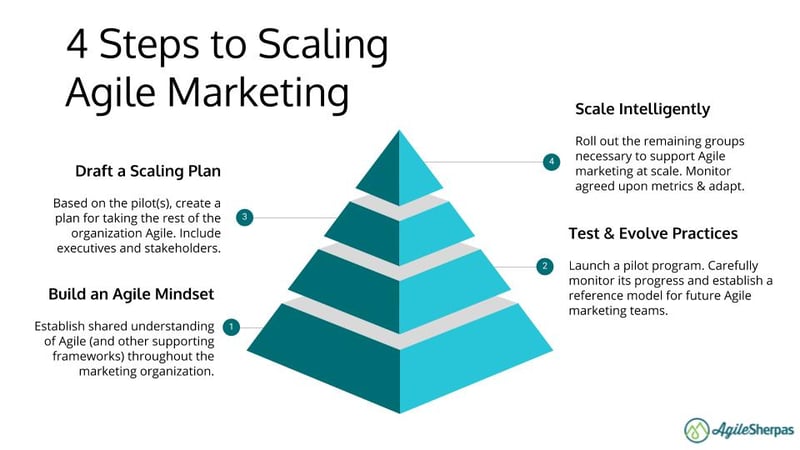

First, we need to point out that scaling agility to multiple teams is never the very first thing you do. As you can see in this diagram, there’s quite a bit of up front work we can’t neglect.

There are essentially four steps to building up your agile marketing scaling capabilities:

- Build an Agile Mindset: You need a firm foundation on which to build your new organization, so this step is crucial. Everyone in marketing needs to understand Agile as a concept so they can support the group’s transition. Ideally this step also includes grounding in other concepts that compliment Agile, such as Design Thinking and Theory of Constraints.

- Test and Evolve Practices: Only once you understand the mindset, can you begin to apply it by establishing actual practices, like backlog refinement and daily standup. Knowing the “why” behind meetings and roles allows you to pick and choose wisely and avoids costly mistakes.

- Draft a Scaling Plan: Whether you’re working with a group of 20 or 2,000, you need a roadmap to guide your scaling effort. The Rimarketing framework is designed to be modular, so you can drop in new groups steadily over time. This tends to be less risky and more effective than transitioning hundreds of people simultaneously.

- Scale Intelligently: Begin to implement your plan, following the Agile principles of inspect and adapt. Monitor your agreed-upon metrics to adjust the plan as you learn more about how Agile really works inside your marketing organization.

Designing Agile Marketing Teams

The next issue that needs addressing is how we set up teams as we scale.

For the love of all that is good and decent, do NOT try to structure Agile marketing teams around short-term projects.

While you CAN maintain functional silos, be prepared to hit a ceiling of improvements within 8-12 months. After that you’re going to need to consider real cross-functional, customer-centric teams to see more benefits.

However, you choose to start, keep your teams small. Three to nine members is a good range, with 4-5 being the sweet spot. These numbers typically don’t include the person responsible for effectively leading the team, aka the Team Lead (clever name, right?).

Who Leads Agile Marketing Teams

The team lead can have almost any traditional marketing title, but they typically come from the senior managerial level or above.

They need at least a moderate level of seniority to effectively navigate organizational politics, and in some corporate cultures to even be allowed in a room with senior leadership. Rimarketing relies heavily on the team lead, so let’s see exactly what this person is responsible for:

Being a stable point of contact

Whenever someone outside the execution team needs something from one of its members, they approach the team lead, who incorporates the request into the team’s existing priorities and commitments, eliminating hallway conversations or surreptitious requests that can result in context switching for individual contributors and derail the execution team’s planned, strategic efforts.

Managing temporary SMEs and shared resources

In even the most well-designed systems, there will be outliers who don’t fall precisely into the execution team structure. In marketing groups these tend to be subject-matter experts (SMEs) who have a skill set that’s crucial to an execution team’s success but isn’t always necessary. The team lead is responsible for making sure that the right SMEs are available at the right time to support their execution team.

Supporting distributed team members

Another inevitable fact of life for the modern knowledge-worker is that some (or maybe even all) of a team won’t work in the same building. When you have a mixed team (some colocated and others distributed), it falls to the team lead to ensure that the environment supports both.

Fact-finding and requirements gathering

An execution team works from a prioritized queue of work. As items make their way to the top, the team lead proactively collects information the team needs in order to start on them. This may mean taking meetings with stakeholders, gathering requirements, or some combination of the two. The most important thing is that execution team members focus their efforts on doing work; the team lead focuses on enabling that execution.

Interfacing with agencies

Agency involvement can vary widely depending on the capabilities of a particular execution team, but the team lead should typically act as the liaison between the execution team and the agency. I say “typically” because in some instances an internal SME is better equipped to work with an agency. In those cases the team lead may pass this particular duty off to an individual contributor.

Doing the Right Work at the Right Time

Missing from the above list is the team lead’s most important responsibility: ensuring that the team does the right work at the right time. This topic gets its very own section because of the impact, for good or ill, the team lead can have in this arena. The activity that produces the magical right work–right time alignment is prioritizing the team queue, or to-do list. This conveys which pieces of upcoming work are most important (they’re at the top), and which aren’t (they’re at the bottom).

The items at the top of the team queue are crucial to achieving its core goals, and they align with the direction in which marketing as a unit is trying to move. Less important or less time-sensitive work falls to the bottom of the queue, freeing up the team from worrying about when those tasks might become relevant.

The Role of the Team Lead

As they prioritize tasks, team leads need to make sure the team has all the information necessary to tackle the most important work. Often this means having meetings with stakeholders, collecting requirements, reviewing past projects for performance data that might affect the plans, coordinating inter team dependencies, and more. As you can imagine, these activities easily fill a workweek, especially when we factor in the team lead’s necessary participation in the strategy group. This heavy workload means that a team lead should not also be asked to perform tasks within the execution team.

Because of this distinction, you may find that existing project managers do well as team leads. Assigning them this role can work, depending on the maturity and performance level of the team they’re working with. Project managers typically have the organized approach and the internal connections needed to collect requirements and liaise with stakeholders, but they may lack the strategic perspective necessary to prioritize the queue, as well as the people-wrangling skills required to effectively oversee a fledg- ling self-organizing execution team.

Marketing director types tend to perform best in this role, although their project-oversight and requirements-gathering skills may be slightly rusty. If you have to choose between project management skills and strategic capabilities in your team lead, favor the latter.

Nail it Before You Scale It

Agile marketing is a long-term project, and you probably won’t ever be really “done” evolving it. But before you embark on a serious scaling effort, make sure you have at least a few fairly high functioning Agile marketing teams in place.

Small problems in teams will be compounded at scale, so make sure you’ve allowed time for these issues to surface and find resolution.

This is why pilots are so crucial; they allow smaller groups within a marketing organization to test the waters and identify the unique roadblocks for using Agile in your company.

The lessons from pilot teams create a reference model for future teams. Reference models aren’t precise blueprints (each team will have their own special spin on Agile), but rather a set of good practices that new teams can follow to set themselves up for success.

Setting Up Agile Marketing at Scale

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s explore what scaling really looks like for Agile marketers.

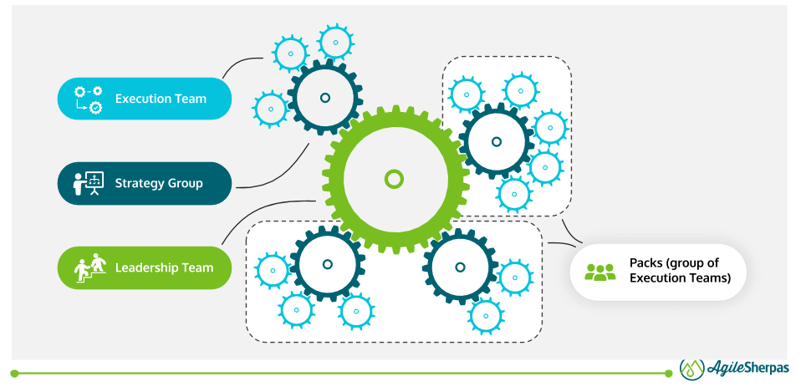

Here’s a generic diagram of a Rimarketing organization:

It has three main components, with a fourth added in the case of large, diverse marketing organizations:

- Execution Teams

- Strategy Groups

- Leadership Teams

- Packs

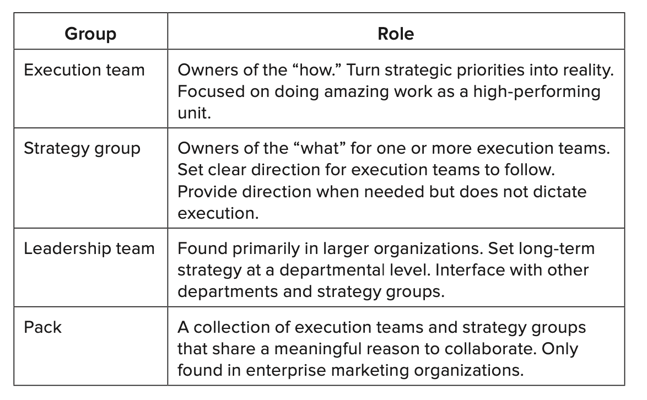

Execution Teams: Getting Stuff Done

Execution teams, as their name implies, focus on execution. Meaning, they rely on others, namely the strategy group, to help direct their efforts.

To enable them to perform at their highest level, we structure execution teams according to the following guidelines:

- Shared purpose: Ideally teams form around the shared goal of delivering value to customers. Their purpose should be overarching and clear.

- A few clear KPIs: One of the most important ways that an execution team achieves high performance is through its ability to say no to incoming requests. Their core KPIs are the filter through which all stakeholder asks must pass; work that won’t deliver on an execution team’s KPI won’t get accepted by the team.

- Owners of the “how”: The leadership team and strategy groups will be asked to own the “what”—to clearly tell others what objectives are crucial to marketing and organizational success. It’s the execution team that gets to own the “how”: the ways they choose to achieve those objectives.

- Cross-functionality: Teams should contain all the necessary skills to execute the work for which they’re responsible. Interdependencies create bottlenecks and delays; avoid them whenever possible.

- Reasonable size: Execution teams are small, ideally between four and ten people. There are options for organizing teams outside this size range, but the research is clear: smaller teams get more done.

- Stable point of contact: One person, the team lead (whom we’ll meet shortly), should act as the buffer between the team and its stakeholders. This role frees up individual contributors to focus on executing outstanding work.

- Strategic connection: The team lead also connects the team to a larger strategy, at both the marketing and organizational levels. Together with the shared purpose, this connection provides a clear North Star for the team to work toward.

- Psychological safety: Teams need to feel safe speaking their minds. Even though that might mean fundamentally disagreeing with leaders or fellow team members.

Strategy Groups: Doing the Right Work at the Right Time

To guide a group of execution teams, we establish a strategy group. This team ensures that when two or more execution teams need to collaborate, they have a shared vision from which to work. Creating a clear, documented, stable strategy also frees up execution teams to get on with the business of doing great work. They don’t need to worry about whether they’re doing the right things because that evaluation has already happened.

Strategy groups can also help remove dependencies and impediments that frustrate multiple teams. Strategy groups are true to their name: they create strategies rather than perform actual marketing tasks.

These groups are not called teams because they don’t function as a true team. They are made up of marketing leaders who set larger, longer-term strategic priorities for one or more execution teams. The team lead should straddle both groups, splitting their time between supporting the execution team and coordinating strategic efforts with other team leads within the strategy group.

Leadership Teams: Steering the Ship

The last level of Rimarketing is the leadership team. Smaller teams may not need to establish this group at a formal level. But, if you have ten or more full-time marketers, a leadership team will benefit you.

This is where year-long strategic objectives are set, critical KPIs are chosen, and, at the enterprise level, interteam and interdivision collaboration gets facilitated. For marketing teams that are accustomed to racing from one campaign to another without an overarching goal, the leadership team is there to help.

Lastly, the leadership team acts as the final arbiter of disagreements between strategy groups. We want to remove empire-building tendencies and leaders’ typical focus on completing their pet projects. Those unhelpful command-and-control behaviors should be replaced by collaborative, team-centric work designed to meet agreed-on strategic objectives.

But from time to time, even the most well-meaning strategy groups disagree on what work the execution teams should be doing.

These conflicts can be healthy, because they surface different perspectives on how to achieve larger goals.

But to gain consensus and execute in unison, the leadership team may need to weigh in to maintain alignment when strategy groups clash.

Packs: Multiple Teams With a Single Purpose

When several execution teams come together around a central strategy group, Rimarketing refers to the configuration as a pack. A medium-sized marketing organization may consist of a single pack; a massive group, like the two-thousand-person organization I’m currently working with, will comprise dozens of packs serving many distinct regions, products, business units, or personas.

Like an execution team, a pack needs an overarching reason to exist. It should be clear who’s in the pack and who isn’t. Each pack requires at least one strategy group—maybe more—to guide the strategic direction of the execution teams that make it up. Ideally each pack will also have a handful of core KPIs to use in evaluating its performance as a unit,

Packs are similar to the tribes outlined in the Spotify model; the primary distinction is their governance. In Rimarketing, a strategy group helps guide the direction of multiple execution teams to steer the pack in the right direction.

Agile Marketing for Enterprise Marketing

As the scope of a marketing team expands, so does the Rimarketing framework. Because of its modular nature, we can add more and more teams, functions, business units, products, etc. over time.

Breaking Down Agile Marketing Team Structure

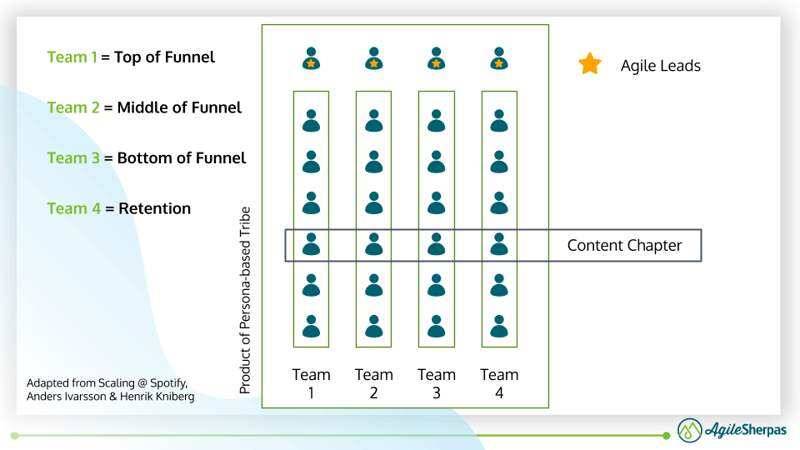

Speaking of packs, let’s end by taking a closer look at one of the modules from the above diagram.

These four teams have a shared purpose -- persona, product, or business unit -- and thus need to have a shared vision and backlog.

We call them a pack, and you may have heard them referred to as a tribe in the Spotify model. Of course, the naming doesn’t really matter. The important thing is that the teams are organized in such a way as to be able to deliver value independently and cross functionally.

That typically happens best when teams are organized by stages of the customer journey. However, you might be able to arrange them according to channel and still see good value coming from each team.

More holistically, the Strategy Group who oversees this pack ensures that they’re pulling towards the same goal, doing high quality work, and most importantly balancing the needs of the customer with the demands of the business.

Scaling Agile Marketing Intelligently

Despite the common usage of the phrase, “Agile transformation,” there is no magic wand that you can wave and become Agile overnight. Scaling takes time, effort, and above all commitment from all levels of the organization.

You can map out a scaling strategy, but be ready to evolve it as teams go through the process and learn more about how Agile marketing really works in your unique situation.

------------

Shu Ha Ri explained (from Mastering Marketing Agility):

The “Ri” in “Rimarketing” comes from the concept of Shu Ha Ri, a Japanese phrase that tracks the progression, in any area of skill, from novice to master.

We begin in the Shu phase, learning and following the rules. Coloring inside the lines, we do what experts tell us to do. As we haven’t yet mastered the fundamentals of the process, we can’t yet make intelligent adjustments to it.

Eventually, at our own pace, we advance from Shu into the Ha phase. We have just enough expertise to bend the rules a little, to get creative. Our actions still fall squarely within the limits of traditional practices, but we’re learning to flex and adapt those practices.

We arrive ultimately at Ri, the phase of creation and innovation. While our activities still connect to, and are recognizable as, the practices used in Shu and Ha, in the Ri phase we invent and create.

Examples of Shu Ha Ri

The world contains many examples of this evolutionary process. Yet, for my money, nothing drives it home quite like the big dance scene at Rydell High in the movie Grease. A national dance show has chosen Rydell as the site of its contest. The students perform their best moves in an attempt to win stardom and glory.

One couple, Doody and Frenchy, are firmly in the Shu phase. Doody can barely follow the prescribed steps of a traditional waltz. “Doody, can’t you at least turn me around or something?” Frenchy pleads, as Doody marches woodenly across the gym floor holding her stiffly in his arms. “Be quiet, French. I’m tryin’ to count.” Shu phase all the way.

Next, during the Hand Jive, lots of kids demonstrate their attainment of the Ha level. Hand Jive has a set of prescribed motions, and many of the couples expand on that foundation. Rather than merely clapping, tapping fists on top of each other, and jerking thumbs over their shoulders, they add moves. Staying with the beat, following the prescribed pattern of executing each move twice, the more experienced dancers comfortably experiment within the framework of the dance.

The camera then moves to Danny and Sandy, the romantic leads (played by John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John). Danny and Sandy also move in rhythm. But, beyond that, they make up everything as they go along, dancing far more inventively than the other couples. They play off each other’s moves, leading and following one another to create a unique series of steps for each song. Like all Ri dancers, they operate creatively and effectively within the boundaries of their given dance tradition. Their actions are built on the fundamentals they learned in the Shu stage. Yet, they look nothing like those basic steps. They’ve evolved far beyond “I’m tryin’ to count.” They are in Ri, flowing, adapting, experimenting, always in the moment, always creating.

Before you leave this page, why don't you pause for a second to get our Agile Marketing Transformation Checklist?

Topics discussed

Andrea Fryrear is a co-founder of AgileSherpas and oversees training, coaching, and consulting efforts for enterprise Agile marketing transformations.

Improve your Marketing Ops every week

Subscribe to our blog to get insights sent directly to your inbox.